The early sixteenth century saw the advance of the Ottoman Empire into Europe. Though the Ottomans remained far away from England to be considered a real threat, the English were still influenced by Ottoman actions. Ottoman technological superiority led to better military tactics, which facilitated raids and invasions in Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean Sea. The Ottomans’ influence in the Mediterranean Sea also grew with their defeat of Venetians at the Second Battle of Leopanto in 1500.[1] By the time Charles I of Spain became Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire as Charles V in 1519, Ottoman pirates were raiding the French southern coast and disrupting trade routes.[2] It was with the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent that the Ottoman Empire reached its zenith and began various campaigns that would unequivocally threaten Christian Europe. The growing conflicts against the Ottoman Empire in Central Europe inadvertently aided Henry VIII in his efforts to reform the English church detailing and help to explain why the rest of Europe made little to no real effort to stop Henry. Continue reading

England

A Comparison of Scientific Advancement in Scottish Universities and the Royal Society

The seventeenth century was a period of exciting scientific growth in Scotland and England. However, the platforms for this progress were different for each kingdom: in Scotland, it was within its universities that new science first took hold, whereas in England, scientific advancement was largely occurring within the Royal Society founded in 1660. The fact that one of these platforms were universities, and the other a private club, led to key differences in the transition and outcomes of scientific growth in the two kingdoms. The universities being a center of scientific inquiry was both a hindrance, due to the ability of church and state to exert control, as well as a benefit to Scotland because it enabled new knowledge to spread to students. While science in the Scottish universities seems to have lagged behind the Royal Society in taking on the new science at first, it accounted for Scotland’s uniquely prominent Enlightenment in the proceeding century, marking a different experience than in England. Continue reading

James VI and I: “Great Britain’s Solomon” or the “Wisest Fool in Christendom”?

The Union of the Crowns of 1603 was an historic event: James VI of Scotland, England’s neighbor and neutral ally since 1560, acceded the throne of England after Elizabeth I’s death, making him James VI of Scotland and James I of England and Ireland. Since James’ rule now extended over three different kingdoms, he aimed to find a way to unify them in order to ensure a solid footing during his reign. However, there have been varying opinions of how effective James was at doing this, but also how competent a king he was in the first place. These varying of opinions are evident when looking at the vastly different epithets that James earned, ranging from “Great Britain’s Solomon” to the “Wisest Fool in Christendom.” These diverging historiographical viewpoints raise the obvious question as to why there are so many varied opinions concerning James and his effectiveness as a ruler. Continue reading

Jacobean Court Perspectives on New World Colonization: 1603 – 1625

To say that the English settlement of the New World was an easy task would be to severely understate the difficulties they met, if not outright fallacious. Starting under Elizabeth, the English experienced the failure of Sir Walter Raleigh’s colony at Roanoke in 1587 and the abandonment of Bartholomew Gosnold’s fort and trading post at Cuttyhunk Island (Massachusetts) in 1602. Granted, the English were successful over time at their Jamestown settlement in Virginia starting under James VI and I’s rule, but the ensuing century is merely a tale of abandonment, consolidation, and abysmal failure for English colonization of the North American continent. Continue reading

15/35, Needed More Restriction

A king is, in theory, the figurehead for the kingdom he rules over. In him, outsiders can see the values the country he resides in and upholds. During times of conflict, he is a man who does not dwell in the safety of his castle, rather he fights with his knights on the front lines. In peace, he is a man of the people, always open to their suggestions and willing to negotiate, never resorting to using force or fear in order to control them. The king is righteous, justice incarnate, and a God-fearing warrior. He does not command respect; rather, he earns it.[1] These values were championed by Thomas More in his definition of a good king, though they would lead to his demise as Henry VIII reshaped those very definitions to suit his own goals. Continue reading

Dissecting a Divorce: King Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon

A pivotal period in the history of the early modern world was King Henry VIII’s schism with the Roman Catholic Church and the English Reformation it sparked. These events led to England’s formation as a Protestant nation, isolated from the influence of Rome. It is believed that King Henry VIII’s request to Pope Clement VII to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon was largely based on his desire to marry a suitable woman of child-bearing age capable of producing a male heir. Although the union of Henry and Catherine had produced a daughter, Mary, the king required a son in order to ensure succession of the Tudor dynasty. King Henry feared a foreign monarch or prince’s marriage to his daughter would result in a foreign power effectively controlling his realm. Catherine’s child-bearing days were nearing an end and many experts declared that she would not survive an additional birth. Continue reading

England’s Empire

The word “empire” commonly holds the connotation of territorial expansion. In early modern Europe, England’s case for empire was unique because Henry VIII established England as an empire, and then further expanded his territory. Henry VIII used Parliamentary statute, the Act in Restraint of Appeals and the Act of Supremacy to make England an empire and to make himself, for all intents and purposes, emperor. Though the way in which England developed into an empire was quite unique, with a strong, centralized government and close relationship between king and Parliament, the English empire grew to be influential in Europe. Henry’s empire demonstrated how the term “empire” evoked both a consistent governmental stronghold as well as territorial sovereignty. It was only after this empire was first established did Henry then expand his imperium with the incorporation of Ireland and Wales. Continue reading

Celtic Lore and James VI and I’s Attempts at Union

In Westminster Abbey, underneath the coronation chair, there lays a plain stone. The stone, commonly known as the Coronation Stone, or the Stone of Scone, serves primarily as the place where English monarchs are crowned. However, before being used by the English crown, the stone was used by the Scottish kings according to legend. During Edward I’s war with Scotland in 1296, the stone was taken as a spoil of war and placed in Westminster Abbey. In the 1328 Treaty of Northampton, one of the terms was the restitution of the stone to Scotland. Despite the agreement of these terms, the stone remained in Westminster.[1] Thus it was notable when James VI of Scotland was crowned king of England in 1603 on this Scottish relic. Continue reading

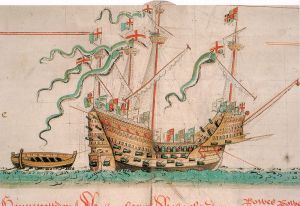

A Tudor and His Navy

As a unified state completely surrounded by water, England needed a strong navy in order to protect against attacks and invasions. Henry VII established the Royal Navy. His son, Henry VIII, continued to strengthen the navy, adding more ships and equipping them with advanced artillery. A strengthened royal navy was borne out of the diplomatic situation brought on by Henry VIII’s separation from Rome. Because of the diplomatic conflicts, and the need to strengthen the navy and its ships, Henry VIII’s reign revolutionized the Royal Navy with style and power. Continue reading